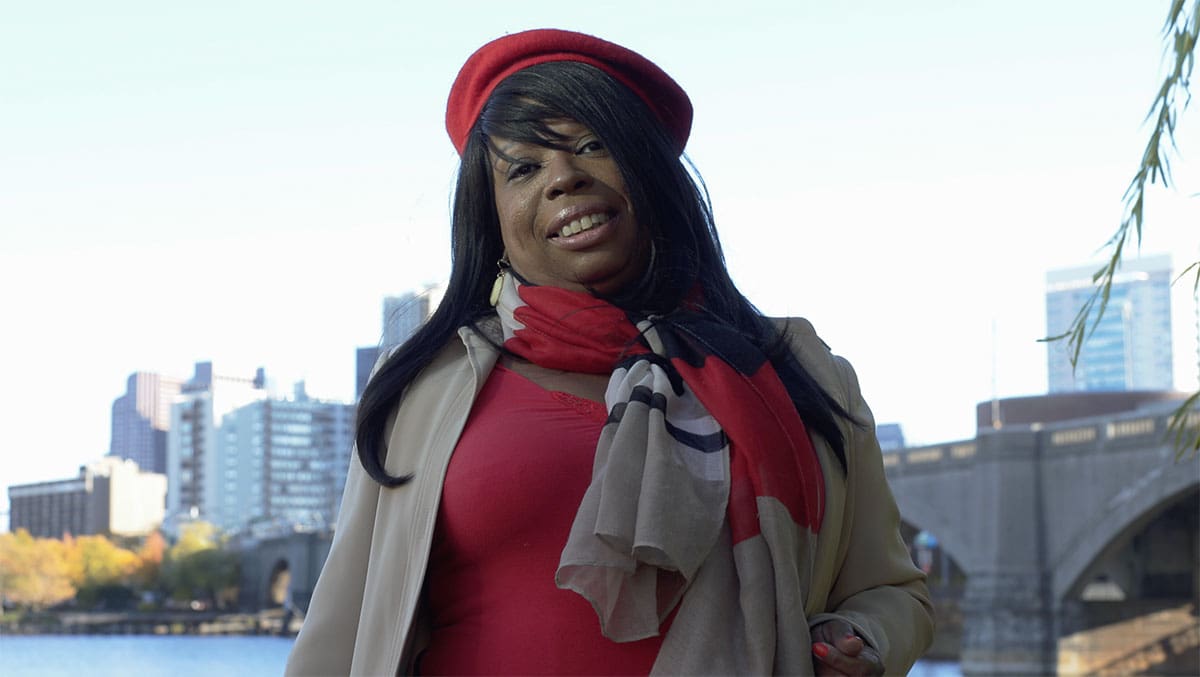

Growing up in Boston’s Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan neighborhoods, Marisa DeLoatch has always had an affinity for public transit. She remembers begging her mother to let her and her sister ride the T by themselves when she was just 10 years old. At 14, DeLoatch attended private school in Watertown by taking the Mattapan trolley to Ashmont Station. “It was so exciting to get on the trolley to Ashmont,” she recalls.

“My mother – as a single, awesome working parent – did not drive, and she never let that hold her or us back,” she says. “We have always relied heavily on the T.” Her mother took the family on weekend trips to the Arnold Arboretum, the Blue Hills Reservation, and even Maine, all using the MBTA. “Those memories are so dear to me.”

DeLoatch has worked with CLF for 28 years – most recently as the organization’s recruitment coordinator – and has lived in West Medford for over 20. Now, instead of the Red Line’s Mattapan trolley, she is excited to ride the new Green Line branches into Boston – a development more than 30 years in the making.

On Monday, March 21, MBTA officials cut the ribbon on its new Union Square branch. Nine months later, on December 12, officials will cut the ribbon on the new Medford Branch, completing a three-decades-long plan to extend the Green Line – a plan often mired by fluctuating costs and timelines.

Staci Rubin, CLF’s vice president for environmental justice, is happy to see the progress spearheaded by CLF, community groups, business owners, and residents. “This will improve air quality and make it easier for residents to get where they need to go in the most efficient and dignified manner.”

Reaching this long-awaited milestone has been a grueling process dating back to the late 1980s. That’s when the planning began for the new Central Artery Project. Ultimately known as the Big Dig, that project aimed to replace the elevated I-93 with a wider underground expressway, extend nearby highways, and create green space.

The Big Dig concerned CLF advocates from the start. Increasing the capacity of highways and tunnels through Boston would attract more cars, worsening air pollution for nearby communities already overburdened by environmental hazards.

CLF met with state officials, calling on them to reduce the adverse effects of the massive highway expansion. In December 1990, CLF and Massachusetts agencies reached a landmark settlement establishing a timeline of significant transportation commitments to benefit residents and offset the harms caused by the Big Dig.

Those commitments included expansions of the MBTA, such as extended commuter rail lines to Worcester and Newburyport and more parking spaces at outer transit hubs. While many of those promised projects finished more or less on time, the Green Line Extension floundered. It was supposed to reach Medford by 2010 – the first of several deadlines that came and went by the time Rubin joined CLF in 2019.

Rubin blames a web of issues for the long delay, namely chronic underfunding and changing administrations that kicked the can down the road throughout the 1990s. Costs rose, and state leaders prioritized system maintenance over capital projects. CLF sued the Commonwealth in 2005 to get the project moving. Thirteen years later, construction finally began in earnest after drastic cost-cutting. “My CLF predecessors continued to hold feet to the fire and raised the need to get the Green Line Extension back on track,” Rubin says.

CLF’s persistent advocacy for the MBTA Green Line Extension reflects the organization’s commitment that public transit needs to work for everyone, particularly for those with no other options. Riders of color, low-income riders, and riders with limited English proficiency suffer disproportionately from a transit system that does not meet their needs.

“We’re constantly advocating for better reliability, accessibility, and affordability,” Rubin adds, noting a high rate of dropped bus trips in communities of color and frequent system-wide fare hikes and service cuts.

For DeLoatch, the community’s and CLF’s demands for better public transportation have helped transform the negative connotations from her youth around public transit and wealth. She emphasizes the health benefits of cleaner buses and trolleys. In reducing climate-damaging emissions, saving on gas money, investing in the local economy, and walking more, “we are wealthy by taking the T,” she says. “We’re seeing a change in the way people think and a change in the way people breathe.”

However, improvements like the Green Line Extension can intensify already widespread gentrification, driving rents up and displacing longtime working-class residents and small businesses with the arrival of major real estate development projects. Renters have seen the “imminent” MBTA Green Line Extension used by property owners to justify rent hikes for years.

“How do we make sure people can stay in their neighborhoods to benefit from this improved transit access?” Rubin asks. “We do not have all the answers, though we are committed to working with community partners to develop solutions.”

Keeping communities engaged in conversation and amplifying their hopes and concerns for decision-makers can alleviate gentrification. “It’s not just CLF at the table; we’re there with residents,” Rubin says.

She points to CLF’s track record on other projects driven by resident concerns, like calling out the Massachusetts Department of Transportation in 2019 after the agency eliminated the HOV lane on I-93 southbound (HOV lanes were another commitment from the Big Dig settlement). That advocacy resulted in the reinstatement of the HOV lane and the establishment of two bus lane pilot programs on the Tobin Bridge and I-93 between Woburn and Medford. “We have this legacy of fighting for big transportation improvements that started with that 1990 Big Dig settlement.”

“The opening of the Green Line Extension is a massive win that we should celebrate. But we need so many more actions to achieve environmental and transit justice,” says Rubin. She highlights the Green Line Phase II commitments to extend the new Medford branch past Tufts University to Route 16 in West Medford – another potential improvement that needs to regain momentum by going through the environmental review process.

CLF advocates are also demanding bus and commuter rail electrification, a low-income fare, and more frequent buses and trains.

Like Rubin, DeLoatch worries about the increasing rents and gentrification that can come with better MBTA service. But she also predicts new opportunities for residents living along the extended Green Line routes. “People of color deserve easy access to jobs, schools and universities, grocery stores,” she says. “The Green Line Extension has been a long time coming, and I am thrilled about it.”

This story was originally published in March 2022. It has been updated to reflect the opening of the Medford Branch of the Green Line.