PART ONE: BREAKING FREE FROM PLASTIC

Personal action alone won’t solve the plastic crisis, but it can lead to a deeper understanding of the problem

by Shebati Sengupta

On the surface, Danielle Ricks is living life just like everybody else. She goes grocery shopping, cleans her house, and grabs a coffee on her way to work. She takes care of her cat, hikes when she can, and goes out to eat with her friends. If you look closer, though, you’ll find Ricks making a series of intentional choices aimed at reducing her impact on the environment.

Those choices add up to living plastic free, a journey that began when Ricks learned about plastic pollution in the ocean. Like many of us, Ricks wanted to know what she could do to help address this growing problem beyond using a stainless-steel water bottle and metal straws. She started wondering what her life would be like without any plastic at all. That’s when she came up with a life-changing challenge – going plastic free for 40 days.

At first, Ricks tried to give up all plastic products, but she quickly realized that would be impossible. They were in her food packaging, her cleaning supplies, her hiking gear. Even her ceramic coffee mug had a plastic lid. In the United States, plastic has become so ingrained in everyday life that you have to step back to notice it’s there. “Becoming aware of the topic,” Ricks advises, “is half the battle.”

So she reframed her strategy, coming up with two rules for herself. First, she wouldn’t throw out any plastic she already had or couldn’t avoid. “I find different uses for the plastic that I don’t have a lot of control over,” she says, including donating or repurposing those products. After Ricks replaced her cleaning supplies with plastic-free alternatives, she gave the old ones to a local shelter. She turned her used almond milk cartons into planters and lined her cat’s litter box with plastic bags.

Her second rule: Avoid single-use plastic. Despite how pervasive plastic is, as soon as Ricks began looking for alternatives, she kept finding more. When she goes out to eat, she brings her own takeout boxes so that she can avoid polystyrene. When she buys vegetables, she puts them in her own net bags instead of in the grocery store’s plastic produce bags.

PART TWO: HOLDING POLLUTERS ACCOUNTABLE

Cities, towns, and taxpayers shouldn’t bear the burden of the plastic problem

by Olivia Synoracki

Plastic has been woven into our everyday lives since the 1950s, when it was introduced during the post-World War II reconstruction boom as a cheap alternative to steel, paper, glass, and wood. Its adaptability and accessibility led to its mass production, normalizing the overconsumption of expendable items and spawning today’s throw-away culture.

An estimated 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic have been produced over the last 70 years – 79% of which has ended up in a landfill or, even worse, been scattered as litter along roadsides, on beaches, and in the ocean, where it persists for centuries.

In recent years, these disposable habits have come under scrutiny as concerns about plastic pollution have spiked. Plastic manufacturers and distributors argue that consumers bear the blame for the accelerating plastic crisis. By pointing fingers at consumer recycling habits, or lack thereof, plastic producers have successfully distracted the public from the real issues with plastic – and the real solutions.

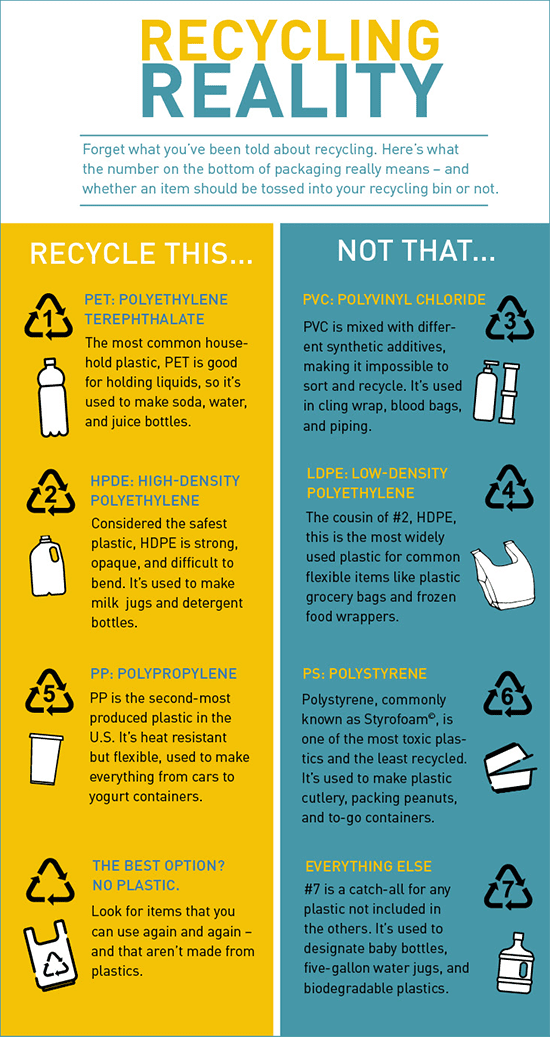

The reality is, says John Hite, CLF’s Zero Waste Policy Analyst, “our country’s recycling system is broken. Much of the waste placed in recycling bins isn’t actually recyclable. Sadly, it’s taken a crisis for people to realize this.”

That crisis was triggered when China enacted its “National Sword” policy in February 2018. Up until then, domestic waste management companies had been shipping much of what was picked up from consumer recycling bins to China. While Americans were feeling good about all the plastic they were recycling, China was just burying or burning much of it on the other side of the world.

Then, the so-called China Sword came down. The country banned waste imports and set strict standards for the plastic it would accept. Suddenly, all of that “recyclable” plastic from America had nowhere to go. What’s more, because China was paying to take all those recyclables, it had provided U.S. cities and towns a revenue stream, which more than covered the cost of recycling programs. “Without Chinese companies importing our trash,” says Hite, “the costs for dealing with it are falling back on communities in the U.S.”

In the nearly two years since China changed its policy, states, cities, and towns across the U.S. have tried to stem the plastic tide by passing a flurry of laws and regulations banning single-use plastics. But those laws will only take us so far. “Cities and towns – and, by extension, taxpayers – should not have to bear the cost burden of dealing with plastic pollution on their own,” says Hite. “Plastic producers must take responsibility for the hazards generated by their products, from their manufacture to disposal.”

The idea of producer responsibility is not new. In the electronic, automobile, and mattress industries, producers are held accountable for the recycling, reuse, or disposal of their products. Many items containing mercury, like automobile switches and thermostats, have also been regulated by producer responsibility laws due to their toxic nature.

Now, with concerns about plastic pollution on the rise, plastic manufacturers are being put under the microscope. If other industries can be made accountable for their waste production under producer responsibility laws – especially when health and environmental risks are involved – why haven’t plastic manufacturers been held to the same standards?

The answer, as usual, comes down to money. The waste management companies that run New England’s landfills and trash pick-up make their profits based on the amount of waste they process. According to CLF’s Zero Waste Project Director Kirstie Pecci, “plastic makes up about 11 percent of disposed waste. If plastic were not disposed of – if a system of actual reduction and recycling were instituted – waste companies would lose hundreds of millions of dollars in New England alone. Because of this, waste companies will fight tooth and nail to stop producer responsibility laws for plastic.”

Plastic manufacturers – ExxonMobil, Dow Chemical Company, and their trade group, the American Chemistry Council – have also lined up against such legislation. Producer responsibility laws would run counter to their plans to spend billions of dollars building new facilities to significantly ramp up plastic production. Their solution to plastic waste? Burn it. The toxic ash, dioxin, and other harmful emissions created when plastics are incinerated are not an impediment so long as the chemical giants continue reaping profits.

Although producer responsibility laws for plastic have not been enacted in the U.S., other countries have taken action. In Europe, companies are required to pay taxes on their plastic packaging, as well as fees for the collection and recycling of those products. The European Organization for Packaging and the Environment estimates that the industry pays €3.1 billion in producer responsibility fees each year.

Passing similar laws in the U.S. will make manufacturers part of the solution to the world’s accelerating plastic crisis. “A system like this would call on manufacturers to invest in design changes that would make products more recyclable, as well as reuse systems that would help cut down on waste,” says Hite. “This will ultimately save cities, towns, taxpayers, and local businesses money.”

Currently, only one New England state – Maine – is considering legislation related to producer responsibility. If passed, the bill will be the first of its kind for New England and the entire country.

Pecci, Hite, and the rest of CLF’s Zero Waste team are determined to put New England at the forefront of the effort to hold plastic manufacturers accountable in the U.S. Building on the momentum of several nation-leading single-use plastic bans passed in the region over the past year (see sidebar below), they are focused on educating lawmakers about the hazardous effects of plastic – from the fracked gas used to produce it to its disposal costs – and the cost burden it poses to local government. It’s through this education, along with testifying at hearings, writing and proposing bills, and collaborating with partner organizations, that the team is laying the path toward a zero-waste future. But its advocacy work doesn’t end there.

The Zero Waste team also meets regularly with community members to educate them about plastic waste and encourage them to advocate for meaningful change by contacting their legislators.

The Zero Waste Team’s efforts serve as a reminder that consumers can help to solve the plastic crisis, but they are not to blame for it. Ultimately, says Pecci, as the plastics industry continues to perpetuate a broken system, all of New England needs to look toward solutions that hold producers accountable. “The mass production of a material that endangers communities and contaminates the climate is simply unsustainable and unacceptable,” she says. “Producers must play their part in solving this crisis.”