In 2015, energy giant Invenergy announced its plan to pave over a pristine forest in Burrillville, Rhode Island, to build a 1,000-megawatt fracked gas and diesel oil power plant. The plant size and scope immediately set off alarm bells at CLF’s Rhode Island office.

With coal plants across New England shutting down, thanks in large part to CLF’s campaign to make the region coal-free by 2020, fracked gas was being touted as a cheap and clean substitute. But gas is still a climate-damaging fossil fuel, one that New England (and the world) needs to stop using to avoid catastrophic climate change impacts.

With an expected life of at least 30 years, the Invenergy plant would lock Rhode Island into climate-damaging fossil fuels well beyond 2050, the date by which the state had committed to cut its carbon emissions to 80 percent below 1990 levels. In November of 2015, the day after Invenergy applied to the state’s Energy Facility Siting Board for a permit, Senior Attorney Jerry Elmer filed a motion for CLF to intervene in the proceedings.

“This would have been a new, long-lived fossil fuel power plant,” says Elmer. “That’s bad public policy. But we really thought hard [about getting involved], because we believed it was unlikely that we could win the case.” The proposal already had the support of the Governor, the Chamber of Commerce, and many town leaders, who eagerly repeated Invenergy’s talking points about the supposedly dire need for the plant.

What Elmer didn’t know then was just how powerful an ally CLF would have in the people of Burrillville. Invenergy, too, would soon learn that it had seriously underestimated the power of community.

“If it wasn’t for the hundreds of volunteers and a broad coalition of amazing groups all around the state, that plant would be sited right now,” says Jason Olkowski, who lives in Burrillville with his wife Erin, who grew up there, and their children. Instead, community members, alongside CLF and other allies, blocked the plant at every opportunity, drawing out the approval process for nearly four years, which strengthened their argument that the plant was not needed in the first place.

The Olkowskis had heard about the power plant proposal when it first was announced but hadn’t given it much thought at the time. When they went to a town meeting to learn more, they found it packed with Invenergy supporters. Most weren’t from Burrillville, yet they dominated the microphone when it came time for the public to comment. Frustrated by what they had seen, the Olkowskis went home and read Invenergy’s 473-page application for state approval.

“We started scanning through the tables of hazardous pollutants that are going to be spewed into the air, the acres of forest to be clear-cut, the 3.6 million tons of carbon dioxide it will emit,” recalls Jason. Surely, the couple thought, if they want to put something like this in their beautiful town, there must be a real need for it.

But as they dug deeper into the hazards of fracking, the dangers of the pipelines and infrastructure needed to transport it, the water wasted to run gas power plants, and fracked gas’s role in climate change, they realized that the Invenergy plant wasn’t just about Burrillville – it all tied into a bigger system that is harming the global environment as well.

As the Olkowskis started voicing their concerns, they were repeatedly told that the plant was a done deal and that there was nothing they could do. But that only galvanized them more. “We had been consulting with lawyers from the town and CLF, so we knew it was far from a done deal,” Erin says.

The Olkowskis soon connected with other community members opposed to the plant, including Kathy Sherman, who lived across the street from the proposed building site with her husband.

Because of their proximity to the site, Kathy and her husband had received a formal notification about Invenergy’s proposal, but details were scarce. They were given a deadline by which they could intervene in the proceedings, but having a seat at the table during the Siting Board’s deliberations came at a price. “We were required to have attorneys to represent us,” Kathy says. “So that seat at the table cost us money. It wasn’t fair democracy.”

Kathy grew more concerned as she learned about the plant, especially its potential health impacts for herself, her husband, and her neighbors.

“Toxic pollution won’t happen in a vacuum over the town of Burrillville. It will impact the entire state, as well as Connecticut and Massachusetts.”

Kathy Sherman, Burrillville resident

As those opposing the plant started to come together, they combined their strengths to tackle the issue from multiple angles. “Once we all rallied together, everyone brought their different expertise and interests,” says Kathy. “We were able to put together a group that took this fight to different levels.”

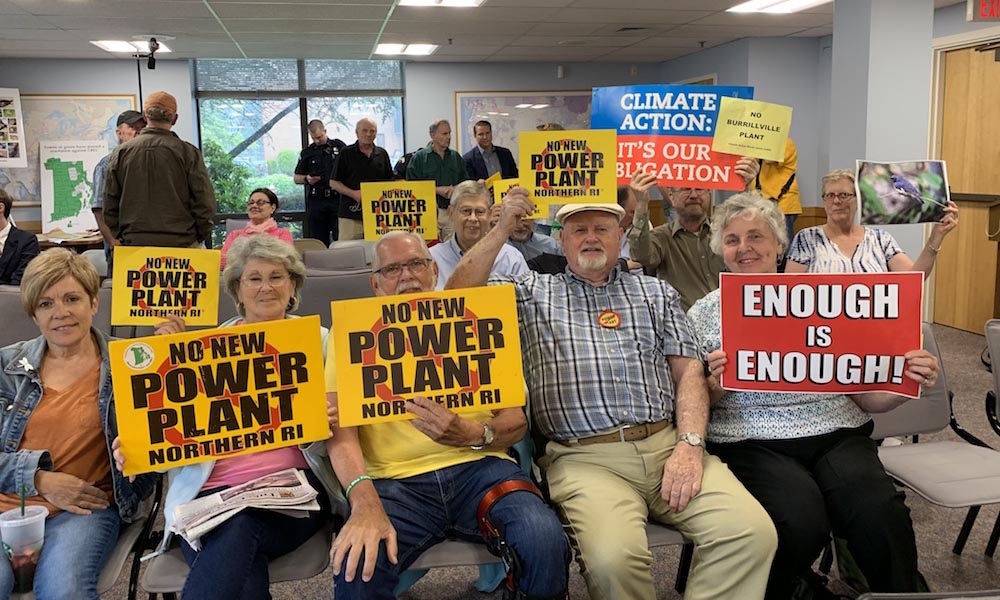

A Facebook page was launched, and fact sheets and signs distributed. Rallies were held, and petitions signed. Residents educated neighbors and town officials about the dangers the plant posed, creating an army of vocal opponents. “If we had a chance of winning, we had to reach a lot more people like us, people who don’t see themselves as activists but who we knew would care once they learned what’s really at stake,” says Erin.

On the other side of the equation, only CLF and the town of Burrillville were at the Siting Board opposing the plant. Local citizen groups were turned away. “The townsfolk needed us as a litigation voice in the proceedings,” says Elmer. Stopping the plant for good could only be done by getting the Siting Board to deny a permit — so CLF helped take on that part of the fight.

“It was a synergistic relationship between CLF and the town,” says Elmer. While CLF fought Invenergy at the Siting Board, “there were things that townspeople could do that were important to the case that CLF could not do.”

One of those things included blocking Invenergy’s water supply. The company intended to use water from the local district, which also served Burrillville residents. But members of the community pressured the Pascoag utility district to walk away. This not only delayed the case at the Siting Board, but also hurt Invenergy’s reputation. Town residents then gathered support from neighboring districts, who also refused Invenergy water.

“Invenergy’s whole case began to unravel on account of the citizen pressure on the Pascoag utility district to not give Invenergy water. That was something that could only be done by local citizens,” says Elmer. “We were much stronger, and ultimately successful, than we would have been otherwise.”

Elmer and his community allies knew the dangers of the Invenergy proposal were more than just a local issue, so they broadened their focus to include statewide and regional outreach. The community activists ultimately gathered letters of opposition from 36 communities in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. Community groups organized bake sales and concerts to raise funds and boost awareness. Other key allies like Paul Roselli led critical efforts to educate Rhode Islanders statewide through “learn the facts” sessions in numerous towns.

Education became increasingly important after Elmer learned Invenergy had been keeping secrets. He spread the word about the company’s underhanded attempts in Washington, D.C., to shift $168 million in costs for the plant onto the families and businesses of Rhode Island.

“Invenergy was lying to the public and lying to the Siting Board while clandestinely litigating in Washington,” he says. “Invenergy’s local lawyers were [also] shocked and had no idea. That really hurt Invenergy. It made them look dishonest, it made them look unreliable, and it caused the Siting Board to suspend the docket until the matter was resolved.”

It was a small but important victory that turned momentum against Invenergy and its proposed plant.

Elmer and the town’s attorney, Michael McElroy, also focused on two key questions the Siting Board would use for their decision: Was the plant needed? Would the plant cause unacceptable environmental harm?

To answer the first question, they showed that Rhode Island – and New England as a whole – had other options for its energy supply, thanks to a bevy of laws aimed at boosting clean, renewable energy in the state. And as the fight against the plant stretched into years – and the date came and went by when Invenergy could hope to meet its original timeline for bringing the plant online – it became more and more clear that the promised electricity was simply not needed.

“This was a tangible result of many years of unglamorous, unpublicized work by a lot of people to pass laws and create incentives for renewable energy, to get funding for renewable energy projects, and to get those projects through local utility commissions,” says Elmer.

Those years of work pushing ahead with clean energy policy and projects were crucial. Because as it stood, the Siting Board had irrefutable evidence that our energy grid is shifting rapidly towards renewables – rendering the Invenergy plant obsolete. It demonstrated how local work makes a big impact, even when it’s hard to see the broader picture.

As for the second question – the plant’s environmental impact – CLF and its partners showed that the plant would disrupt a critical wildlife corridor. They showed that this exact area had been rejected for development before because of its ecological importance – a clear sign that a new, long-lived power plant would cause unacceptable harm to the ecosystem.

A sobering vision of what was at stake if CLF and its allies lost the fight against the plant could be found in Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania, where another Invenergy power plant went online in January 2019, its smokestacks spewing harmful pollution into the air. This sister plant also faced opposition. But unlike Burrillville, the people of Jessup – the town that now hosts one of the largest gas plants in the U.S. – were divided, and community opposition was overruled. They lacked the complementary efforts of local action, an ally like CLF, and years of work to get cleaner energy on the grid. As a result, “by the time the Siting Board in Rhode Island was making its decision about the permit for Invenergy, the Lackawanna plant was already operational,” says Elmer.

When the fight against the Invenergy plant started in 2015, Elmer, the Shermans, and the Olkowskis had no idea they would still be fighting it in 2019. “But it’s been time well spent,” says Erin. “And it’s been encouraging to see so many other people helping and collaborating, coming together across the state and the region.”

All those years of hard work came down to a final hearing of Rhode Island’s three-member Energy Facility Siting Board late last June. The packed room filled with a tense silence as the Board announced its decision: permit denied.

Cheers erupted as the Burrillville residents in the room rejoiced at the outcome – a testament to the persistence of local heroes who refused to give up and go home.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Conservation Matters Annual Report in summer 2019.