Boston-based Vicinity Energy is the largest district energy provider in the U.S. and the first to innovate its new carbon-free "eSteam" boiler. Photo: Courtesy Vicinity Energy.

Last year, Emerson College marked a big milestone on its journey toward clean energy. The college, with the help of the Boston-based district energy firm Vicinity Energy, committed to heating its entire Boston campus using carbon-free steam for heating.

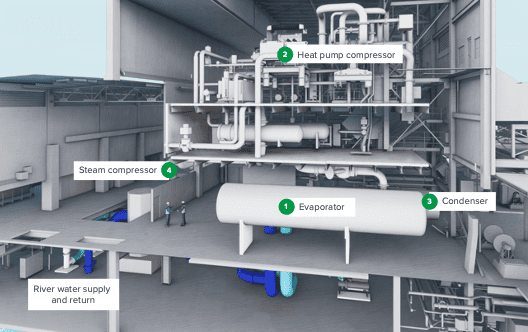

It signed on, in fact, to “eSteam™” – Vicinity’s latest innovation in district heating, which involves heating or cooling a collection of buildings connected to one central source. Combining three technologies – heat pumps, electric boilers, and thermal storage – Vicinity says it will change the game on sustainable district energy. The vision is still unfolding, but when it’s done, it will look like this: Vicinity will buy renewable, carbon-free energy generated by offshore wind, solar, and hydro. A mammoth heat pump at Vicinity’s power plant in Cambridge’s Kendall Square will use that electricity and water from the Charles River to produce steam. Meanwhile, an electric boiler will also create high-pressure steam using renewable electricity. Steam created by the heat pump and boiler will travel through a network of underground pipes until it reaches the Emerson campus rimming the southeastern corner of the Boston Common. The steam heat will ultimately warm Emerson’s dormitories, assembly spaces, classrooms, and offices. And all this, without fossil fuels.

“By offering buildings a reliable, carbon-free thermal energy product, we are going to have a profound impact on the city’s building emissions and a profoundly positive reduction of city emissions,” says Matt O’Malley, chief sustainability officer at Vicinity. (O’Malley has a history of thinking about the city’s emissions. Before joining Vicinity, he was a Boston City Councilor and supported legislation requiring buildings over 20,000 square feet to reduce their carbon pollution by 2050.)

“During this time when there are rollbacks of so many of these important regulations at the federal level, it truly is up to cities and states to lead in this,” he says.

Emerson is not the only organization to jump aboard Vicinity’s clean steam project. Life science real estate development company IQHQ has also signed on for its Fenway Center Phase 2 development. Other contracts are currently being negotiated, says O’Malley. Vicinity’s 42-megawatt electric boiler went online in November 2024, delivering carbon-free thermal energy to Boston-area customers, but the complete setup will not be in place until 2031. An incremental timeline, with the 35-megawatt river heat pump being completed in 2028 and the thermal storage unit in 2031, is an advantage, says O’Malley.

“That allows us to embrace new technologies,” he says. The idea, he says, uses “existing infrastructure, marrying it with new and emerging technologies so that we can deliver decarbonized thermal energy to over 75 million square feet of buildings that we serve in Boston and Cambridge alone. And we are replicating this at many of our other [power] plants throughout the United States.“

A Short History of District Heating

Vicinity Energy is the largest district energy provider in the United States. The four-year-old company is a subsidiary of French private equity firm Antin Infrastructure, which bought the assets of the former district energy firm Veolia in 2019. Today, Vicinity operates 19 district energy systems in 12 cities, serving 975 buildings across the nation. In New England, Vicinity operates only in Boston and Cambridge, where Vicinity’s 29 miles of pipe snake through downtown Boston and Kendall Square, bringing steam to clients that include the Prudential Center and Northeastern University.

Such large entities – colleges and universities, hospitals, airports, and office parks – are ideal candidates for district energy systems, which may sound space-age but date back to Ancient Rome.

The idea was modified centuries later by Birdsill Holly, who in 1877 created the U.S.’s first district energy system, using a centralized coal-fired steam boiler to distribute steam heat to several buildings surrounding his own home. From there, district heating became a common feature in compact cities in the U.S. and Europe. These systems used coal-fired steam boilers to heat buildings, which were connected by underground pipes.

District Energy Sheds Its Dirty Past

Over time, most of these systems transitioned from coal to oil, and later to natural gas. Today in the U.S., more than 600 district energy systems operate on military bases, healthcare facilities, manufacturing and industrial facilities, and even on newer campuses like Meta, Apple, and Google. The vast majority still use fossil fuels, but more than 40% use combined heat and power (or cogeneration systems), which may include in addition to gas, some renewable fuels. MATEP (which stands for Medical Area Total Energy Plant) is one example in Boston, servicing five hospitals in the Longwood Medical Area. Its tri-generation plant, also known as CCHP, produces electricity, heat, and cooling in a single facility, although it still uses natural gas. Its production of electricity also functions as a microgrid, operating independently of the main grid.

District energy systems, which can both heat and cool, are popular, says O’Malley because they are reliable. “We operate at 99.99% reliability,” he says.

They also offer economies of scale, making them more efficient and cost-effective than onsite boilers. Even those fueled by fossil fuels emit less carbon because they typically use less fuel than onsite generators. According to the United Nations Environment Programme, district energy systems “typically reduce primary energy demand in heating and cooling by 50%” and can achieve operational efficiency of up to 90%.

A Better Way with eSteam

No doubt, the savings and reduction in carbon emissions attract many customers, but the vast majority of district systems in the U.S. still rely on fossil fuels. This is something Vicinity wants to change. It is committed to transitioning to a carbon-free district energy system powered by clean energy. That’s where, says O’Malley, the “three-pronged approach” of heat pump, electric boiler, and thermal storage comes into play.

New England, says O’Malley, is the perfect place to begin this transition, in part because of the availability of wind power.

“New England really is the Saudi Arabia of wind,” says O’Malley. “The conditions of where we’re located make it an ideal location for wind farms.”

A Shift in Prospects with a New Administration?

Vicinity has big plans, but what does the Trump administration mean for a business that had banked on the continued development of offshore wind? Today, you could say there are real headwinds.

“Nevertheless, we are confident and committed to supporting offshore wind development, particularly off New England,” maintains O’Malley.

Despite the current administration’s backtracking on climate and environmental goals, O’Malley says that Vicinity’s customers are still eager to transition away from fossil fuels. They remain committed to a clean energy world. And so, too, is Vicinity.

“The decarbonization plan is happening across the board,” he affirms. “We’ve got this. I think it’s safe to say that a year from now, four cities [Baltimore, Grand Rapids, Michigan, Boston, and Philadelphia] will either have fully operational electric boilers or will be very close to having them. The work will have begun.”

This is one of an occasional series on New England’s energy innovators.