CLF’s Clean Water Enforcement Project Holds Polluters Accountable, One Business at a Time

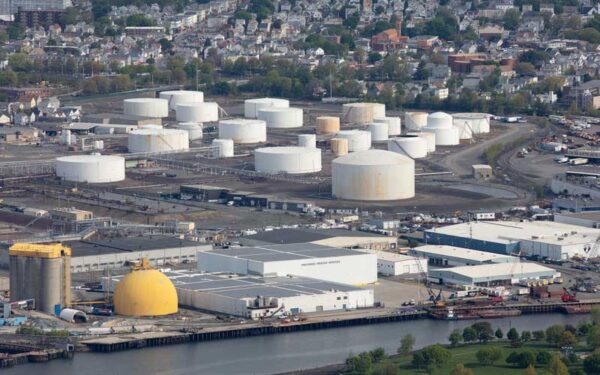

A boat trip through the Mystic River Watershed – which spans 76 square miles and 22 communities north of Boston – reveals scenery both beautiful and troubling. A great blue heron gracefully taking flight contrasts sharply with hulking freighters offloading cargo. It’s the most urbanized watershed in Massachusetts and one of the most polluted. So when a neighborhood group approached CLF in 2010 with concerns about stormwater runoff from a large scrap metal facility, the organization agreed to take a closer look.

“At this facility, there were towering mountains of scrap that were much higher than the privacy fences that surrounded them,” said Zak Griefen, CLF’s Environmental Enforcement Litigator. When rain and snow falls on those scrap piles, the runoff drains into the Mystic River, carrying pollutants from those metals with it. This facility, said Griefen, “didn’t have and never applied for a permit to discharge pollutants, so it was blatantly in violation of the Clean Water Act. When we looked at similar facilities nearby, we found that none of them had the required permits, either.”

That initial research led to the recogni- tion of a much larger and serious problem all across New England: Thousands of industrial sites, from small boat marinas to sand and gravel pits to junkyards, line the shores of the region’s inland and coastal waters. And, while many of them discharge waste into those waters, few hold the permits to do so legally. The pollutants coming from these unregulated facilities – lead, zinc, and phosphorus among them – are some of the most toxic and damaging to our waterways, many of which, like the Mystic, are already severely compromised from industrial pollution and contamination.

The impacts of this unchecked pollution run deeper than the harm to individual waterways, however. “Without permits, these facilities are flying under the radar of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and state regulators,” said Christo- pher Kilian, Director of CLF’s Clean Water and Healthy Forests program. “These agencies are working to clean up our public waters, and they rely on self-reported information from industry to implement the law. When a large chunk of that community isn’t permitted, that creates a gaping hole in the data being used to make decisions about the health of our waters.”

“We can bring these industrial facilities into compliance with the Clean Water Act, and protect our inland and coastal waters.” — Zak Griefen, CLF Environmental Enforcement Litigator

At the same time, the sheer volume of unpermitted polluters makes it difficult for EPA to go after them on its own. “Enforcement officials need all the resources possible to address these violations,” said Kilian. “That’s why Congress created the citizen lawsuit provision of the Clean Water Act,” which allows citizens, and organizations like CLF, to file suits directly against facilities that are violating environmental laws. “Our work is augmenting government enforcement efforts,” said Kilian.

In 2010, CLF filed citizen suits against five of the polluting facilities along the Mystic River. By 2012, those cases had been resolved and CLF, under the auspices of its newly formed Clean Water Enforcement Project, moved on to file complaints against more industrial polluters in Massachusetts. Suits in New Hampshire and Connecticut followed, with approximately 45 cases initiated throughout New England to date.

Most of the suits are resolved through negotiated settlement agreements rather than trial, and CLF is already seeing results from the work. “Within a year or two of a settlement we’re able to see significant reductions in the amount of pollutants being discharged,” said Griefen. Even as the cases are fostering improved water quality, they also serve as a warning to other facilities that are either ignoring or unaware of the requirements of the law. “Many of these facilities have been operating this way for decades,” said Griefen. “Right now, there’s no economic downside to not complying with the law. We want to change that, to create a very significant financial downside to noncompliance that will incentivize other facilities to clean up their act voluntarily.”

A crucial component of the settlements is that the facility owner or operator must make a payment towards a supplemental environmental project, or SEP, which funds environmental and restoration projects run by local nonprofits in the impacted watershed or community. So far, the cases have generated nearly $320,000 in payments to support a dozen projects, from Everett and Salem in Massachusetts to Long Island Sound [see below].

With thousands of industrial facilities throughout New England still illegally dumping pollutants into waterways, Kilian and Griefen know that the task ahead is not an easy one. But they are determined to keep at it. “CLF intends to protect New England’s waterways and hold polluters accountable for their rampant violations of environmental regulations,” said Griefen. “We can bring these industrial facilities into compliance with the Clean Water Act, and protect our inland and coastal waters as fishable, swimmable, and drinkable public resources.”

Giving Back to the Community

When suits are settled, CLF holds violators financially accountable in a unique way. Instead of paying the government a penalty, businesses can fund a supplemental environmental project, or SEP, which will benefit public health and the environment. The SEP provision has become a key component of CLF’s Enforcement Project.

In the Mystic River Watershed, where the Project began, SEP funds are being used to measure the river’s phosphorus levels – too much phosphorus causes toxic algae blooms, promotes invasive plants such as water chestnut, and chokes oxygen supplies needed by fish and other species.

“We need to reduce the amount of phosphorus being put into the Mystic River,” said Katrina Sukola, watershed scientist for the Mystic River Watershed Association. To do so, the group is developing a calculation, called a total maximum daily load, of how much phosphorus the river can receive and still meet water-quality standards. The responsible parties will be asked to reduce phosphorus in stormwater over a period of time to meet this benchmark. “This will be a legally binding agreement that holds municipalities and industries responsible for reducing pollutants,” said Sukola. “It’s one of the best ways to clean up the river.” Developing the calculation is a multi-year process, but the SEP grant is helping to kick off this costly effort by funding necessary equipment and lab fees.