A diver measures kelp with a triangular frame while diving Cashes Ledge. Photo: Jenny Adler

In summer 2025, a team of scientists and photographers undertook an expedition to Cashes Ledge. Cashes is an extraordinary region deep in the Gulf of Maine that’s known for its towering underwater mountains, rich kelp forests, and abundant marine life. The expedition’s participants dove to explore the vibrant environment, document fish and seafloor communities, collect samples of kelp, photograph the remarkable underwater creatures, and take measurements for further study. This was the first visit since CLF nominated the region to become a national marine sanctuary and the latest in an ongoing effort to monitor the health of the kelp forest and overall ecosystem.

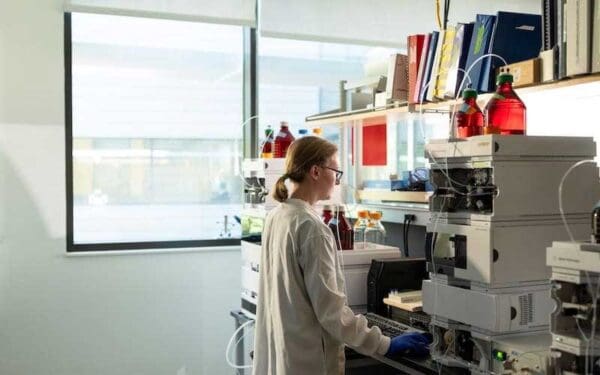

After the trip, CLF’s Senior Scientist Dr. Gareth Lawson sat down with Dr. Jon Witman and Dr. Robbie Lamb, both scientists and professors, as well as Dr. Jenny Adler, an underwater photojournalist, to talk to them about their experience. They discussed the uniqueness of Cashes Ledge, its value to the ocean ecosystem, and why it desperately needs protections. We’re sharing the edited interview, which has been condensed for length and clarity, as well as photos from the dive.

Gareth: What first drew you to Cashes Ledge?

Jon Witman: When I was an undergraduate student, I had an opportunity to join the Manned Undersea Science and Technology expedition to Cashes in October 1977. We were underwater during an intense snowstorm in October – you know, the old days when the Gulf of Maine was cold – and I had about half an hour in the kelp forest on top of Ammen Rock, and that’s all it took. I was hooked. Huge kelp, tons of fish, teeming with cod. I’ve been going back whenever I could ever since.

Robbie Lamb: The ocean continues to harbor deep, dark, and unexplored places that we have very little information about, and it seems to me that it’s sort of the frontier of exploration and discovery left to us on Earth. Just the knowledge that this was deep and far offshore, and few people had been there, was a big attractor.

Jenny Adler: I have this obsession with kelp forests. I grew up in Massachusetts, and I had no idea that that was out there, even being someone who was really obsessed with kelp. Jon calls it “the living museum of the Gulf.” Now I’m also completely hooked.

Gareth: What makes Cashes so unique and important?

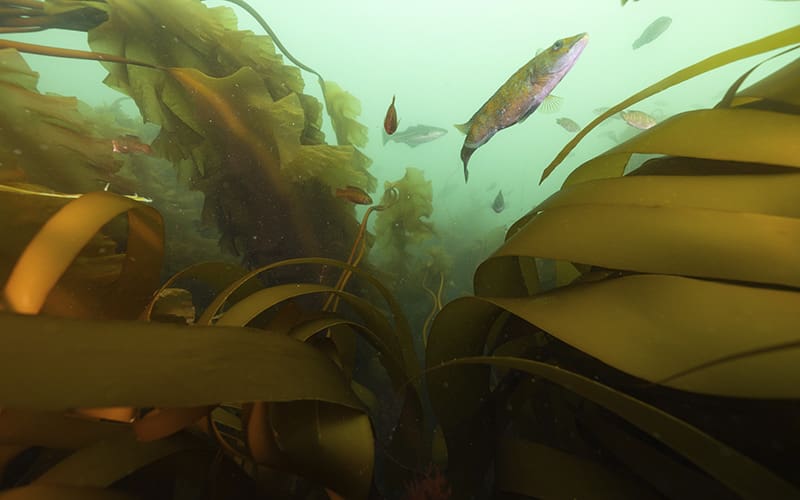

Jon Witman: The huge kelp forest on the undersea rocky ridge, which comes within 10 meters of the surface. Considering that it’s like 150 kilometers offshore, it’s really unusual. The bottom becomes covered with invertebrates, so it’s like an invertebrate garden. There are sponges, lots of sea anemones, all sorts of other invertebrates. Cashes Ledge has at least six different habitat types supporting unique species in each. We’ve shown that in some of our comparative surveys that Robbie and I have done, there’s basically 300 times more fish on Cashes Ledge than at the same depth in the coastal zone.

Robbie Lamb: This last trip, I think we got something like a 24, 25-foot-long kelp frond, which blew out of the water any record that we could find for these species in the Gulf of Maine.

We’re also seeing really high numbers of fish out there, in particular cod, which used to be the mainstay of New England’s economy. Legend has it that you could lower a basket with rocks weighing it down over the side of your boat in the Gulf of Maine and reel it back up without any bait or anything, and it would be wriggling with cod.

So, to be able to go to Cashes Ledge today and predictably find cod, every single dive – they’re not exactly wriggling in full baskets as you pull them up off the side of the boat, but they are there, and they are relatively abundant. This is a holdout, sort of a remnant for cod populations in the Gulf of Maine that could actually be repopulating other parts of the Gulf that have been overfished for decades.

Gareth Lawson: Why should we protect Cashes?

Jon Witman: It’s a productivity hotspot. We want a healthy Gulf of Maine, right? So, to do that, we need to provide productivity to feed the food web. So that’s what Cashes does. It’s an oasis of high productivity. We believe it’s a nursery for commercially important species. Our work hasn’t focused on that so much, but it’s not a leap to suggest that it fosters the population increase of species that are commercially important.

The other reason is that it’s a biodiversity hotspot. And like Noah’s Ark, we want to preserve the Gulf of Maine biodiversity, particularly at this time, when ocean biodiversity has been declining. It’s one of the last refuges of high Gulf of Maine biodiversity in the offshore area. It’s completely unique and begs to be permanently protected.

Another reason to preserve it is that it serves as a natural living laboratory for studying climate change in the Gulf of Maine. As you know, the Gulf of Maine is warming faster than anywhere else in the world’s oceans.

Jenny Adler: I think even if people don’t know that it’s there, it’s important to protect places that are still … maybe not fully pristine, but an example of what the Gulf looked like years ago.

Robbie Lamb: It’s good to also have these stories of hope, places that appear to be resilient, that appear to be healthy, to give us motivation to keep working and striving to keep these places healthy and to continue conserving wild places.

Gareth Lawson: What did you see? What was new, surprising, exciting?

Jenny Adler: We saw basking sharks! It was really cool.

Robbie Lamb: They move surprisingly fast.

Jenny Adler: They’re so fast! Robbie and I saw a goosefish at the end of our dive, which was just as wild. It looked almost like a pancake with all these frills coming off of it.

Robbie Lamb: I looked up, and this thing is just sailing above me. That was really special. We also saw a Mola mola, a sunfish, which I had not seen before.

It’s rare to go to some patch in the ocean and see all that life. It’s not there by random chance. These are species that are either attracted to the Cashes Ledge because of the habitat it provides, or because of the food it provides. It’s all connected, and you can feel it. Cashes Ledge is the key to all of that. It’s a unique and special place.

Gareth Lawson: What did you see that worried you? What sort of threats face Cashes Ledge?

Jenny Adler: I had only been out there this one time on those couple dives, and I think what was wild to me was that Jon and Robbie mentioned they hadn’t seen [as much invasive] red algae up until this point. The kelp is still doing decently well, but to imagine the red algae wasn’t there before was pretty wild, because it was prevalent.

Jon Witman: Invasive red algae. It’s all over the place on the [sea floor]. The other thing is cod densities. Cod are present [but] they’re kind of like the kelp – less abundant.

Gareth Lawson: On balance, are you feeling hopeful? Were there things that were especially encouraging?

Robbie Lamb: People have their eyes on the Gulf of Maine because satellite records and surface buoy records tell us globally that this is one of the fastest warming bodies of water in the global ocean. And what we’re seeing at Cashes Ledge is that the kelp and fish communities are pretty stable over time. Since we’ve been going there regularly since 2014, there haven’t been any big changes. There is a bit of an increase in the abundance of an invasive algae, but that doesn’t seem to be reducing the proliferation of sugar kelp.

The cod population continues to be pretty stable. This could be a bit of a nursery for cod, and it could be a seed population, or a source that can repopulate other areas of the Gulf of Maine. These are fish that are heavily overfished elsewhere, and having this refuge allows them to grow and be healthy, giving them a chance to reproduce. So those were really promising things to see.

Jenny Adler: Just the density of fish when you’re swimming through. I kind of felt like it was almost this tornado of fish that you were swimming through. Even in the kelp forest in California, I’d never experienced that number of fish.

Jon Witman: I am feeling hopeful. Despite the fastest warming in the Gulf of Maine, the kelp forest has retained its ecological structure. Is it changing? Yes, of course. It’s thinning, but it’s taller. Still a remarkable, unique place.